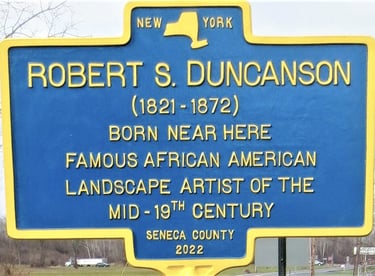

Robert S. Duncanson

Born 1821 in Fayette, New York

Died December 21 1872 in Detroit Michigan.

Buried at Woodland Cemetery Monroe, Michigan

One of the greatest landscape painters in the western United States was an African-American born in Fayette. Although he was beloved by 19th century audiences around the world, this artist fell into obscurity, but a century later has been celebrated as a genius.

He was the grandson of a freed Virginia slave. In 1828 his family moved to the “Boomtown” of Monroe, Michigan. His father John established a profitable house painting and carpentry business. Robert and his four bothers helped in the business, Robert honed his skills on ornate trim and signs, in 1838, he established a painting and window glazing business with partner John Gamblin. Robert really wanted to be a landscape painter and about 1840 he moved to a black neighborhood in Cincinnati, Ohio. Often referred to as the “Athens of the West” because of it’s strong arts community. Cincinnati provided its free black population with a greater access to opportunities for advancement than other parts of antebellum America.

Duncanson became a traveling portrait artist, finding work in Cincinnati, Detroit & Monroe. He developed his landscape painting skills by painting scenes of the Ohio River Valley. By 1842 his paintings were being exhibited in the Cincinnati area. His family could not attend the showings because of their race, his mother was quoted as saying “ That’s ok I know what they look like & where they are, that’s all the matters”.

His first significant painting was “Cliff Mine, Lake Superior”, in 1848 commissioned by abolitionist clergyman Charles Avery a trip of nearly 800 miles from Cincinnati to Copper Harbor Mi.

That painting and the 1851 “Blue Hole, Flood Waters, Little Miami River” established his status as one of the region’s most important painters.

Nicholas Longworth, another abolitionist and wealthy Cincinnati landowner, commissioned Duncanson in 1851 to paint eight elaborate landscape murals to adorn the Longworth family estate, Belmont. That estate today is the Taft Museum of Art and Duncanson’s paintings are one of the biggest pre-Civil War domestic murals in the United States. This assignment was the largest and most ambitious of his career and provided him with the money to finance a trip to Europe to expand his artistic skills and knowledge. In 1853 Duncanson went on a nine-month tour of England, France and Italy, along with his friend and fellow landscape artist William Sonntag. This trip to Europe was the first by an African-American artist. The time he spent among intellectual artists and committed slavery opponents on these European trips spurred Duncanson’s abolitionist feelings.

In the years before the Civil War he increasingly donated paintings to abolitionist causes and participated in several demonstrations and activist rallies. Just as the Civil War broke out in 1861, Duncanson completed what many critics and historians believe to be his “magnum opus,” “Land of the Lotus Eaters.” Inspired by Tennyson and Homer, this large landscape is populated with blacks attending to the needs of white soldiers and was hailed as a “prescient masterpiece of the struggle to save the union and end slavery.” Because of the Civil War, Duncanson left the United States and spent two years in Canada and then went to Europe.

In Europe he was welcomed again by the artistic and aristocratic communities. The Duchess of Sutherland, whom received Duncanson’s painting from her friend, American actress Charlotte Cushman, The Countess of Essex, The Queen of England even purchased some of his paintings. Duncanson visited Alfred Lord Tennyson, England’s poet laureate, at his home on the Isle of Wight and Duncanson brought with him “Land of the Lotus Eaters,” which was partially based on a Tennyson poem. Tennyson was delighted by the painting and remarked, “Your landscape is a land in which one loves to wander and linger.” “The Land of the Lotus Eaters” eventually came to be owned by the king of Sweden. Duncanson became quite enchanted with the Scottish highlands, of which he made a series of landscapes in the 1860s. An 1871 painting, “Ellen’s Isle, Loch Katrine” is hailed as the artist’s final masterwork. This painting was inspired by Sir Walter Scott’s poem “The Lady of the Lake.” and is currently housed at The Detroit Institute of Arts Museum.

In the late 1860s, Duncanson began to suffer from dementia, although he remained in good health physically. He was prone to sudden outbursts, erratic behavior and delusions to the point that by 1870 he imagined he was possessed by the spirit of a deceased artist. Some scholars suggest that the brooding mood and turbulent waters of his seascape paintings, such as “Sunset on the New England Coast” and “A Storm off the Irish Coast,” reflected his disturbed mental state. His symptoms, as described by Duncanson’s cotemporaries, led to speculation that his condition was caused by lead poisoning, probably the result of large quantities of lead paint he used for his house painting work early in his adult life and then for many years as an artist. Despite his failing health, in 1871 he toured the United States with several historical works, priced upward of $15,000 apiece.

His condition steadily worsened until he was placed in a sanitarium in Detroit, following a violent seizure in October 1872. He died there on Dec. 21, 1872.

Though dozens of Duncanson’s paintings survive in art institutions and private collections, after his death in 1872 his name faded into obscurity.

Seven of Duncanson’s paints can be seen at The Detroit Institute of Arts Museum. He is Buried in Monroe’s Historic Woodland Cemetery at Fourth and Jerome streets. He was Buried with other family members in an unmarked graves. In 2019 a local artist & The Detroit Fine Arts Breakfast Club held fundraisers and purchased a large grave marker created by Leo LeClair.

In 2021 The Robert S. Duncanson Society was formed to recognize his 200th birthday.

Summer 1849 location unknown